Good Day

I like to begin by thanking mary Boek for inviting meTo do this presentation –

On the role music plays in early Speech acquisition. And I must say the more I worked on this presentation the more I came to realize what a fascinating topic this is

Music is more than just a melody—as you’re about to see, it serves as a bridge to speech and language.

Speaker Note – Introduction

My name is John Burke. I’m a speech-language pathologist and an ASHA Life Member, with nearly 30 years of clinical experience.

I’m married, a father of three, and a grandfather to four.

The photo on the slide is from a baseball game I attended with my grandson Harvey.

Over the years, I worked with children and adults on:

• Articulation

• Speech

• Cognition

• Swallowing

I’ve worked with a wide range of individuals, including:

• Children on the autism spectrum

• Children with Down syndrome

• People with spinal cord injuries

• Stroke survivors

For the last 10 years of my career, I focused on early intervention—doing home visits with children ages birth to three.

I retired in 2008. These days, I spend time with my grandchildren and work on SpeechTherapy.org, where I share what I’ve learned over the years.

I worked with all ages, but always took special note of my time with very young children.

As teachers, you know how significant—and sometimes dramatic—those early changes can be in a child’s life.

Some thoughts that immediately come to my mind…

1. Natural Engagement

Children are naturally drawn to music. It’s as if it’s written into their DNA.

Whether they’re singing, clapping, moving to a beat, or simply swayin

you can see it in their bodies before you hear it in their voices.

This kind of engagement doesn’t need to be taught.

It happens spontaneously—joyfully—and that’s what makes it such a strong foundation for learning speech and language.

2. Instant Connection

Mention a familiar song—The Wheels on the Bus, Baby Shark, even a simple lullaby—

and watch what happens. NChildren light up.

Their eyes widen. Their bodies perk up. They’re in.

It’s almost universal. Music creates a near-instant connection that draws them into the activity—often regardless of the song or their speech ability.

That kind of quick engagement is something we rarely get in other types of therapy.

3. It’s Communal

Music brings people together—children, therapists, parents, and teachers alike.

When we sing or move with children, we become part of the their moment.

4. Neural Growth

And here’s the science behind the magic:

When children sing, dance, or participate in musical play,

they’re not just having fun.

They’re building real neural pathways— for speech, language, and memory.

Music activates both the left and right sides of the brain.

This integrated activity supports early speech in ways that are measurable, and lasting

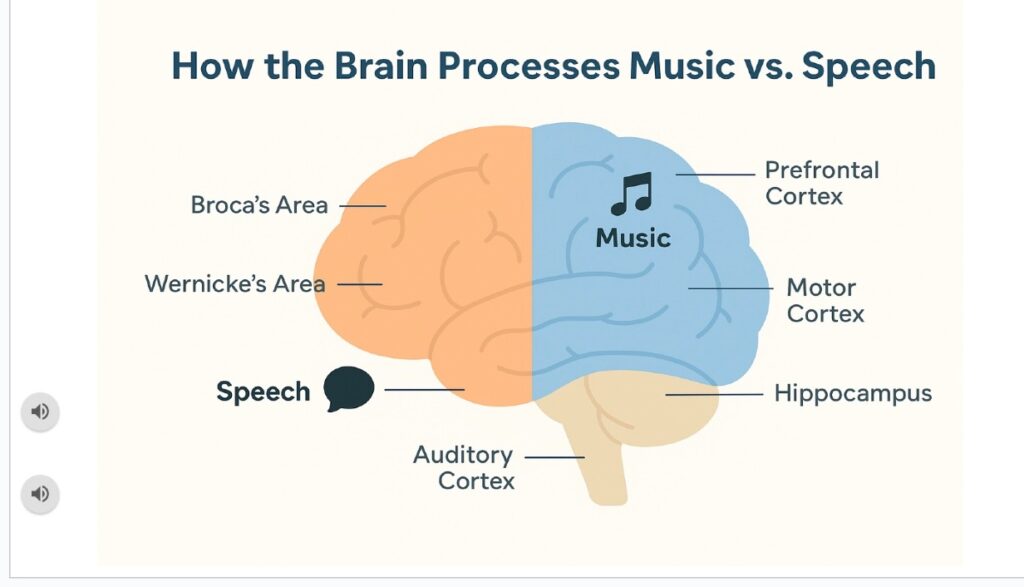

The Brain and Music:

Speaking of neural connections—

let’s take a moment to look at this brain slide together.

You’ll notice it’s divided into two main halves: the left side, shown in orange, and the right side, in blue.

Let’s start with the left side, which is considered the brain’s language center.

- There’s a region called Broca’s area. That’s what helps children get their words out. It’s involved in the motor planning of speech.

- Just below it in this slide is Wernicke’s area—this area helps children understand what they hear. It’s where language starts to make sense.

- And in the middle, we have the auditory cortex. It’s working constantly, helping us tell sounds apart—like hearing the difference between “bat” and “pat.”

Now let’s shift to the right side—in blue.

This is where we process emotion, rhythm, and melody—all the elements of music.

- The motor cortex lights up when children clap, march, or tap to a beat.

- The prefrontal cortex, right behind the forehead, handles planning and decision-making—and it also plays a role in memory.

- And then there’s the hippocampus, deep in the brain. That’s where musical memories and language memoriesare stored—often side by side.

Now here’s the part that still amazes me after all these years:

When a child sings something as simple as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,”

both sides of the brain light up.

- The left side is working on logic and language—choosing the words and putting them in order.

- The right side is handling emotion, pitch, and melody—bringing life and feeling to the song.

That’s why music is more than just fun—it’s a full brain workout, especially for developing speech.

That simple lullaby you’ve known for years?

It’s actually a powerful tool for building the neural pathways children need for speech, language, and even literacy later on.

Now I was going to play a recording of “Twinkle, Twinkle” for you—

but I have a better idea.

If it’s all right with you, let’s unmute ourselves for a moment—and sing it together.

And as we do, I want you to really notice what you feel:

Not just your voice… but your body, your memory, your breath, your rhythm.

You’re not just using one part of your brain—you’re using all of it.

That’s the power of music.

It invites the whole brain to show up—

which is exactly what we want when helping children learn to speak.

Why This Matters for Speech Development

Let’s take a moment to talk about why music is such a powerful tool in speech development.

- Music activates multiple areas of the brain—including the parts that handle language, movement, memory, and emotion. That means when you sing with a child, you’re lighting up much more than just their ears.

- It gives children a multi-sensory way to connect. They’re hearing the melody, feeling the rhythm, seeing your gestures, and often moving along. That kind of experience helps make language stick.

- Some children may not respond to words alone—but they’ll respond to music. I’ve seen children light up when they hear a familiar tune, even if they’ve been quiet all day. A song can be the bridge that helps them begin to express themselves.

- Every time we sing, we help build and strengthen the brain pathways that support speech. And the more those pathways are used, the stronger they become.

Simon’s Story: The Power of Music in Speech Recovery

Simon’s Story: The Power of Music in Speech Recovery

Simon was 65 when he had a stroke.

After that… he couldn’t speak. Not a single word.

His diagnosis was verbal apraxia.

HSe understood everything we said to him—his thinking was sharp—but he just couldn’t get the words out.

His brain knew what he wanted to say, but the signals to his mouth simply wouldn’t connect.

One day during therapy, I brought in my Casio keyboard.

I sat down and began to play “We Shall Overcome.”

And then something happened that I’ll never forget.

Simon—who hadn’t spoken a word—sang every single lyric.

Not just one or two lines—the whole song.

His voice was clear, on pitch, and perfectly in time with the music.

That was the moment I truly saw the connection between music and speech in action.

You see, while much of spoken language is stored in the left side of the brain,

melody and song lyrics often live in the right hemisphere—

the same side that’s sometimes left untouched after a stroke.

This experience opened the door for a therapy approach called Melodic Intonation Therapy, or MIT.

MIT is a research-based technique used to help people with non-fluent aphasia or verbal apraxia.

It uses melody, rhythm, and tapping to help individuals say words and phrases by engaging those musical pathwaysin the brain.

We might start with something as simple as humming or intoning short phrases—

then gradually shape those into real speech.

And for people like Simon, this kind of approach can be life-changing.

It reminds us that even when speech seems lost,

the music inside may still be there—waiting to lead the way back.

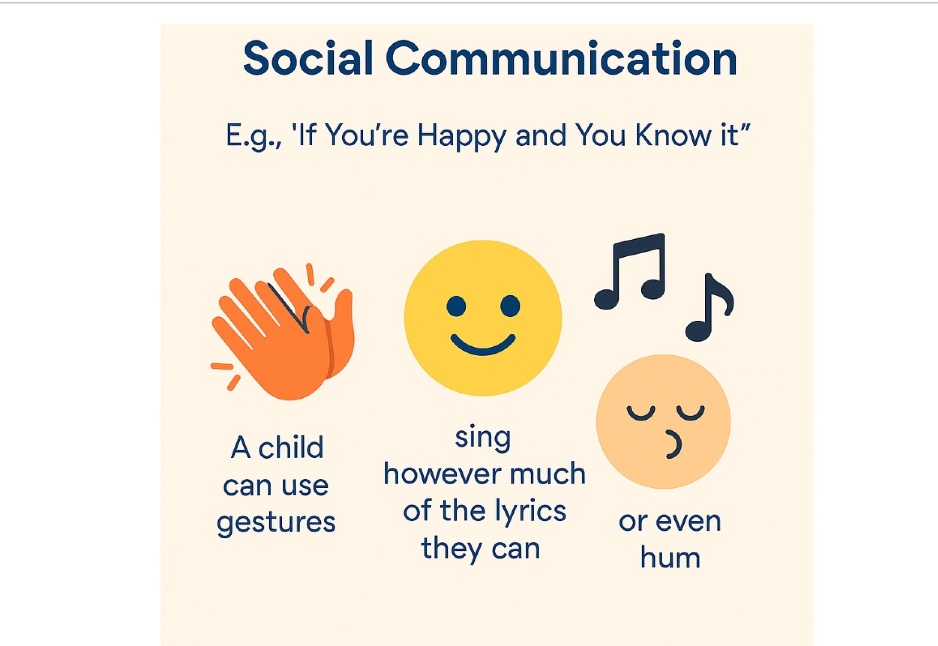

A Safe, Inclusive Space

Music activities offer something truly special:

a safe, inclusive space where every child has a role—

whether they sing, clap, move, or just listen.

There’s room for everyone in the music.

I remember working with Lucas, a young boy who was

nonverbal and very quiet in group settings.

During circle time, we sang “If You’re Happy and You Know It.”

And while Lucas didn’t say a word,

he began to tap along to the beat.

Over time, tapping turned into clapping.

And then, one day, out of the blue—Lucas said, “Happy.”

It was just one word.

But it was his word.

And it came from a place of joy, safety, and connection.

That’s the power of music.

It creates an environment without pressure—

where children can participate at their own level.

There’s no “right” way or “wrong” way to join in.

Some children sing loudly.

Some move their bodies.

And some—like Lucas—begin by simply tapping a finger on their knee.

Every form of participation is valued and celebrated.

In this kind of atmosphere, confidence grows.

Children begin to understand that they are part of something—

that they belong in the group,

even if they don’t use words yet.

Music becomes a bridge:

a way to connect with others and with their own voice.

It’s where shy children find courage.

It’s where quiet children realize they have something worth sharing.

In this safe musical space,

every child’s participation matters—

whether it’s a whisper, a clap, or a full song.

Michael just wasn’t ready

/Michael had just turned three. I was working with him and his mom at their home in Jersey City.

He struggled with airflow sounds— like “p” and “f.”

That day, one of my goals was to have him toot on a toy horn. It’s a fun way to build the breath control needed for those sounds.

We sat together upstairs in their duplex. I tooted. His mom tooted.

Then we gave the horn to Michael. He held it… and gently set it down beside him.

He just wasn’t ready. And that was okay.

Succeeding on his own terms

Michael quietly took the horn, went downstairs—and a few seconds later, we heard it: a loud, proud toot.

He came running back up with a huge smile. His eyes were bright with excitement. You could see the pride written all over his face.

We smiled too and asked, “Can you do it again?”

So he ran back down—and tooted again. This time even louder.

Sometimes all it may take is one sound, one small success, to build the confidence to try something new.

And in this case, Michael just needed some space. Away from watching eyes. Away from expectations.

Downstairs became his practice room. His safe space to experiment. To succeed on his own terms.

Connecting with Others

Songs with Movement: More Than Just Fun

When children act out animal movements during songs like Old MacDonald,

they’re not just having fun—they’re learning how to connect nwith others.

When they flap like chickens or moo like cows, something important is happening:

They’re watching the group, taking their turn, and responding in real time to the music and to one another.

It may seem like simple play, but in these moments, children are practicing some of the most essential early communication skills.

They’re learning how to:

- Take turns—waiting for their cue and joining in at the right time

- Imitate—watching how others move and doing it themselves

- And share focus, or what we call joint attention—tuning into what someone else is doing and joining them in that experience

These are not just motor skills or music skills.

They’re the building blocks of social communication—

the same skills children need for conversation, group play, and classroom learning later on.

And here’s what makes it even more powerful:

It’s not scripted.

There’s no pressure to “get it right.”

It’s a shared experience—one that’s joyful, spontaneous, and engaging.

So when a child flaps their arms like a duck or shouts “moo!” with the group,

they’re not only expressing themselves.

They’re learning how to be part of a community—how to connect, respond, and belong.

And that’s where real communication begins.

Helps Build Confidence

- One of the most important things I’ve learned as a therapist is this: If a child doesn’t think they can say a word— they usually won’t.

- Confidence is everything when it comes to speech.

- I’ve seen children who know the sounds. They understand the words. But they hold back because they’re afraid of getting it wrong.

- Fear of failure can be paralyzing for young speakers. They’d rather stay silent than risk making a mistake.

- Music gives children a safe space to try new things and succeed.

- In a song, there’s no judgment. There’s no pressure to be perfect. If you miss a word, the melody keeps going. If you sing off-key, it’s still music.

- Songs become practice sessions without the practice pressure. Children experiment with sounds. They play with words. They build confidence one note at a time.

When a child succeeds in song, they start to believe: “Maybe I can do this.” That belief becomes the foundation for all future communication.

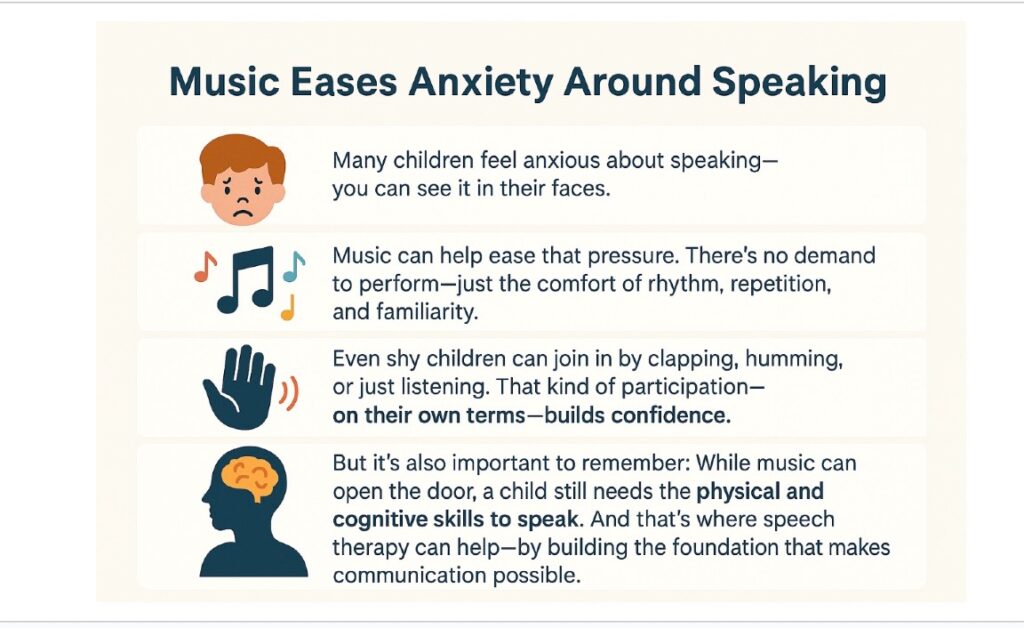

Many young children feel anxious about speaking

They may worry about getting the words wrong, being corrected, or not being understood. That anxiety can cause them to stay quiet—even when they know what they want to say.

Music reduces that pressure.

Songs are predictable. The rhythm and melody give children something steady to follow. The words are already known and repeated, which creates comfort and familiarity.

There’s no pressure to perform.

Children can join in at their own pace. Some may sing, others may hum, clap, or just listen. All of these count as participation. There’s no right or wrong way to be part of a song.

Small successes build confidence.

When a child joins in—even just a little—it boosts their sense of ability. That feeling of success helps reduce fear and builds trust.

Singing is a shared experience.

Everyone joins together, so there’s less focus on any one child. This makes it easier for shy or hesitant children to take part.

Over time, music creates comfort with speaking.

Children begin to explore sounds, rhythm, and language in a relaxed way. Music opens the door to sp

Teaching Turn-Taking Through Music

Turn-taking is one of the earliest social skills tied to communication—

and music offers a gentle, effective way to teach it.

In a simple drumming song,

where children take turns tapping their names to the beat—

they’re doing much more than just playing.

They’re learning to:

• Wait their turn

• Watch others

• Respond when it’s their moment

That’s what we call shared attention in action—

a skill that helps form the foundation for conversation.

The rhythm of the song gives natural cues:

“Now it’s your turn… now it’s mine.”

And because the activity is fun and low-pressure,

children engage—without feeling put on the spot.

They’re not being told to take turns—

they’re simply doing it as part of the music.These small social moments—

listening, waiting, responding—

are essential building blocks for:

• Conversational timing

• Peer interaction

• Group participation in school and play

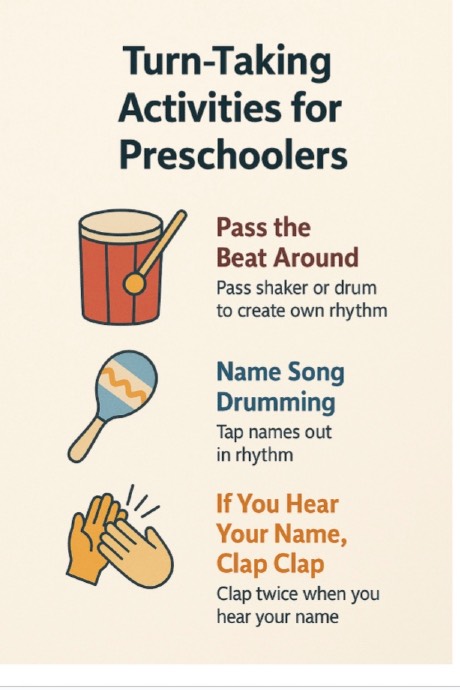

Three Turn Taking Activities

Now—here are three preschool songs that work beautifully for turn-taking:

1. “Pass the Beat Around”

Children sit in a circle and pass a shaker or drum.

Each one takes a turn to create their own rhythm,

before passing it on.

2. “Name Song Drumming”

Each child taps their name in rhythm:

“Ma-ry, Ma-ry” or “A-lex-an-der, A-lex-an-der.”

It’s playful, personalized,

and helps connect names to sound patterns.

3. “If You Hear Your Name, Clap Clap”

The teacher sings a line and names one child at a time.

Only that child claps twice when they hear their name—

a simple way to build listening skills

and self-awareness.In each of these songs,

children are doing more than making music—

Sounds

Songs give children a fun, low-pressure way

to explore speech sounds.

Take a simple tune like:

“Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

It naturally includes key sounds like:

• /r/ in row

• /m/ in merrily

• /b/ in boat

• /t/ in stream

Because the rhythm is slow and steady,

children can hear each sound clearly—

and they’re more likely to try them out on their own.

You don’t need special songs to do this.

You can even make up your own words

to match the sound you want to target.

For example:

“Ride, ride, ride your bike”

helps children practice the /r/ and /b/ sounds.

Just one phrase—repeated to a familiar tune—

can give lots of sound practice in a fun way.

Alphabet songs also work well.

Try singing something like:

“S is for Sunshine, S is for Sun,

S makes the /s/ sound—let’s say it for fun!”

Children hear the target sound

again and again,

in a playful way.

That’s the magic of music.

It gives children repeated practice with sounds—

without pressure.

Vocabulary

Songs introduce new words in ways that are fun, repetitive, and easy to remember.

They pair language with movement, pictures, and real-life meaning—

which makes the learning stick.

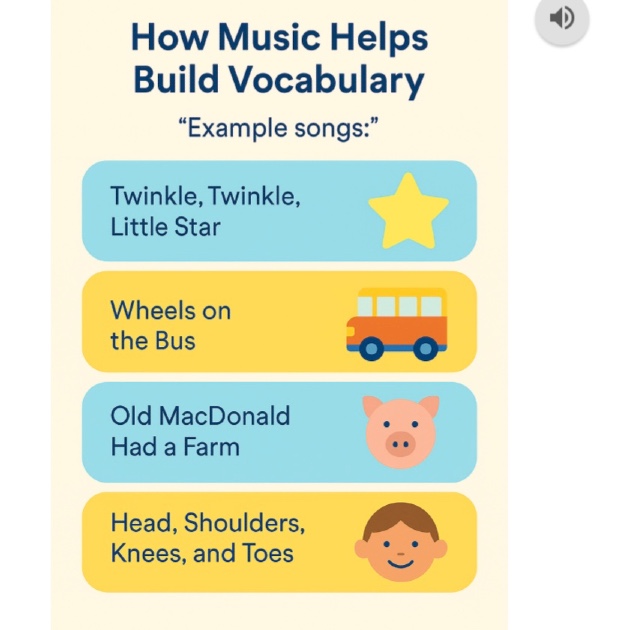

Here are a few classic songs that build strong vocabulary skills:

“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”

Words: star, sky, diamond, night, world, above

This song introduces abstract ideas—like things we see in the sky—while using soothing rhythm and repetition.

“Wheels on the Bus”

Words: wheels, bus, door, wipers, horn, driver, baby, people

Children learn about parts of a vehicle, the people inside, and everyday actions—like “go up and down” or “go swish.”

“Old MacDonald Had a Farm”

Words: cow, pig, duck, horse, sheep—and animal sounds like moo, quack, oink

This song helps children build a category—animals—while learning both nouns and the sounds animals make.

“Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes”

Words: head, shoulders, knees, toes, eyes, ears, mouth, nose

Perfect for teaching body part vocabulary—especially when paired with movement and pointing.

These songs don’t just teach random words.

They help children:

- Group words into categories (like animals or body parts)

- Learn action words (like clap, go, open)

- Understand concepts like up/down, loud/quiet, fast/slow

Because songs are repeated often—and paired with visuals and movement—

they give children lots of meaningful exposure to new vocabulary.

Phrases and Sentences

1. “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”

We start with a simple, predictable phrase:

➡ “Old MacDonald had a farm…”

Then it builds:

➡ “And on that farm he had a cow…”

➡ “With a moo moo here, and a moo moo there…”

This helps children learn sentence parts—who, what, and where—in a fun, rhythmic way.

They’re learning subject + verb + object, with real descriptive detail.

2. “The Wheels on the Bus”

Starts with a phrase:

➡ “The wheels on the bus…”

Then adds an action:

➡ “go round and round, all through the town.”

This teaches verbs, prepositions, and sequence.

And because it changes with each verse—“doors go open and shut,” “wipers go swish, swish, swish”—it shows how sentence structure stays the same even when the details change.

3. “This Is the Way We Brush Our Teeth”

Every line starts the same:

➡ “This is the way we…”

Then adds a daily action:

➡ “…brush our teeth, wash our face, put on shoes.”

This models everyday sentences with clear subject-verb-object structure.

Children can start to say what they do—like:

➡ “This is the way we eat our lunch.”

➡ “This is the way we go to school.”

Bottom Line:

These songs don’t just teach words—they teach how words go together.

Phrase by phrase, line by line, kids start using the patterns they sing to build the sentences they speak.

Pitch and Intonation: “The Itsy Bitsy Spider”

One of the very first ways kids begin to use language

is through pitch and intonation—

how our voices naturally go up and down when we speak.

And this song is perfect for that.

When they sing:

➡ “up the waterspout…”

and

➡ “down came the rain…”

they’re not just saying words.

They’re hearing the melody…

and feeling the emotion behind it.

That rising and falling pattern lays the groundwork for expressive speech.

Even if they don’t know all the words yet,

they’re already learning one of the most important tools in communication—

how tone adds meaning.

So when you sing “Itsy Bitsy Spider,”

you’re not just teaching a song—

you’re helping a child’s voice find its shape.

You sing and note the rise and fall of speech in your voice. Then just say the same words in conversation – without melody – and see how the same pitch exists in melody and your spoken words as well.

Prosody

Prosody is more than pitch. It’s the rhythm, stress, timing, and melody of speech.

Kookaburra is a great example. It has a steady beat. Natural pauses. And fun stress on words like “laugh” and “merry.”

Singing it helps kids hear how language flows. Where to pause. Which words to emphasize. And how to sound expressive.

When children sing “Kookaburra sits in the old gum tree,” they naturally pause after “tree.”

They stress the word “merry” in “merry king of the bush is he.”

This musical phrasing teaches them that speech has rhythm. That some words are stronger than others. That pauses give meaning.

Children who struggle with flat or monotone speech often benefit from singing first. The melody guides them to use ups and downs in their voice.

Songs become practice sessions for expressive speech. Kids learn to make their voices interesting. To emphasize important words. To pause at the right moments.

When they transfer these skills to regular talking, their communication becomes more engaging and easier to understand.

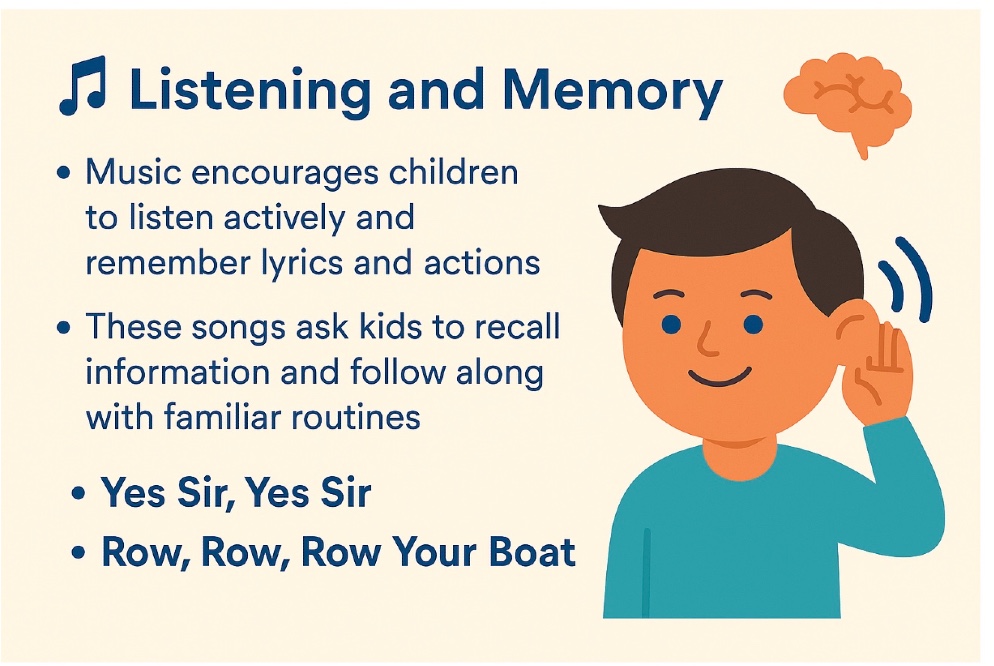

Ways Music helps Listening and Memory

Songs help children learn to listen. They tune in to hear what comes next. When to clap. When to join in.

Phrases like “Yes sir, yes sir, three bags full” or “Gently down the stream” let kids predict what’s coming. That builds listening and memory.

Over time, they start to remember whole songs. Verses, motions, and all.

And what’s interesting— lyrics and melody get deeply rooted in our minds.

Think about it. You probably still remember songs from your childhood. Word for word. Note for note. Even songs you haven’t heard in years.

This happens because music and language together create stronger memory paths. The rhythm acts like a filing systemfor words. The melody becomes a memory cue.

When children learn “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” they’re not just memorizing words. They’re building listening skills. They’re learning to hold information in their mind. To sequence sounds and phrases.

These listening skills transfer to everyday talk. Children who can follow a song can better follow directions. Kids who remember verses develop stronger memory for classroom learning.

Movement and Speech

For kids who are nonverbal,

or who have motor planning issues like apraxia,

action songs offer a way to join in—

without pressure.

“Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” is a great example.

Even if they can’t speak,

they can touch, move, and follow along.

That movement activates both the motor and language areas of the brain.

It gives the child a role—

a way to connect and be part of the moment.

Over time,

As confidence grows and motor patterns develop,speech often begins to follow.

As a speech therapist,

I often used gesture and sign language

as a way of promoting early speech.

While speech issues were still being sorted through.

Sometimes hard to know what a child is thinking

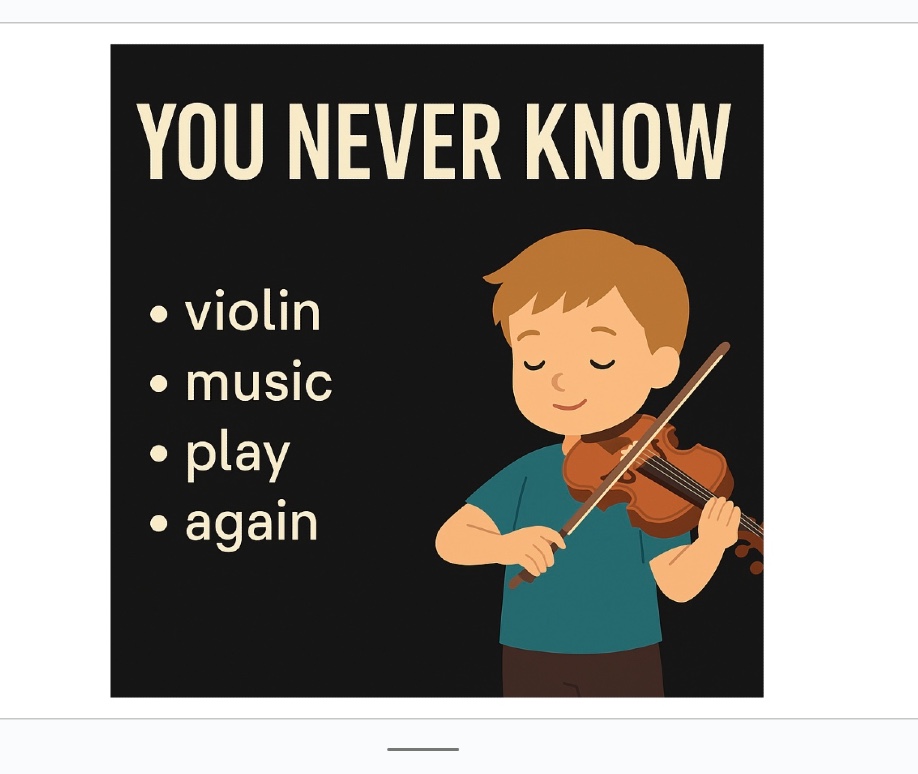

Zachary was three years old and had a significant speech delay.

I was working with him in his home—and no matter how many music activities I introduced, he showed no interest.

We tried everything:

➡ The Wheels on the Bus

➡ This Is the Way We Brush Our Teeth

➡ Five Little Ducks

Nothing connected.

Then one day, I spoke with his mom.

She told me that whenever classical music came on the television, Zachary would stop what he was doing and just watch.

She said he especially lit up during violin solos—he would mimic the bowing motion with his arms, completely absorbed.

So, we followed his lead.

We found a real child-sized violin—something that actually made sound—and we brought it into therapy.

That simple shift changed everything.

Zachary began to engage. He held the violin, moved with it, and even hummed along.

From there, music took a place in his speech development—and in his life.

Some of his first emerging words during this time were simple, meaningful ones:

➡ “violin”

➡ “music”

➡ “play”

➡ “again”

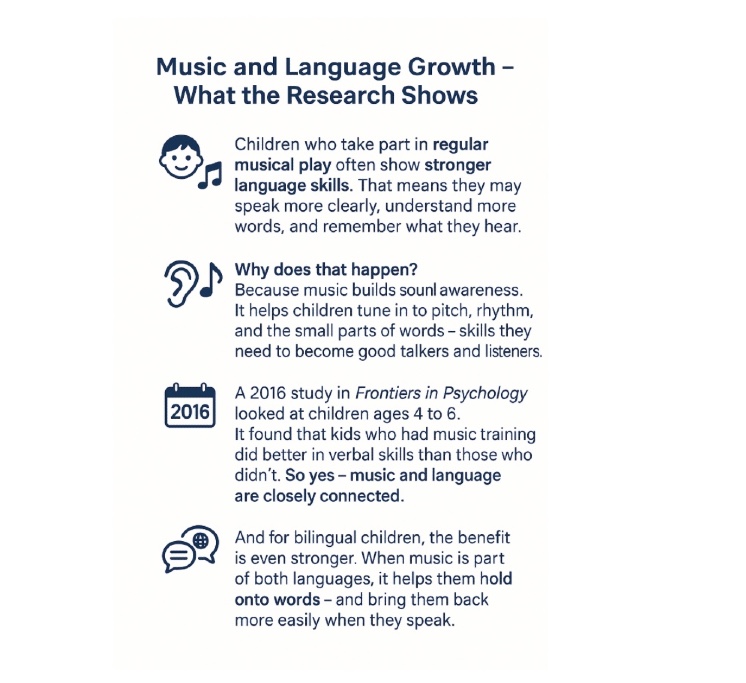

Music and Language Growth: What the Research Shows

Children who engage in regular musical play often show stronger language development. They tend to speak more clearly, understand a broader range of words, and remember what they hear. But why does music make such a difference?

Music helps build a child’s phonological awareness—the ability to hear and play with the sounds of language. Songs with rhythm and rhyme draw attention to syllables, pitch, and word patterns. These are the very skills that form the foundation for speaking, listening, and eventually reading.

One key study published in Frontiers in Psychology (2016) followed children aged 4 to 6. Researchers found that kids who received weekly musical training—simple group singing, rhythm games, and movement—showed significantly better verbal memory and vocabulary than their peers. They weren’t learning language directly—but music helped prepare their brains to process it more efficiently.

Other studies echo these results. A 2020 meta-analysis from Developmental Science reviewed dozens of studies and concluded that musical experiences enhance early language outcomes—especially when paired with movement and social interaction. Music taps into both hemispheres of the brain, engaging areas responsible for speech, auditory processing, motor coordination, and emotional connection—all at once.

And for children growing up with two languages, music may be even more powerful. Bilingual children exposed to songs in both languages often show stronger word recall and pronunciation skills. Why? Because music acts like a bridge—it links the sound patterns of both languages in a fun, repeatable format. When a bilingual child sings a familiar song, the melody becomes a retrieval cue that helps bring the words back.

We see this in practice every day. A child who struggles to answer a simple question might suddenly sing all the right words in a favorite song. For children with speech delays or limited vocabulary, this can be the first step toward expressive language. And for shy or anxious children, music often feels safer than direct conversation—it invites them to join in without pressure.

The beauty of music is that it doesn’t require perfection. There’s no test, no score—just rhythm, repetition, and joy. That low-pressure environment is exactly what young children need to explore language at their own pace.

So when we sing songs like Twinkle, Twinkle, The Wheels on the Bus, or If You’re Happy and You Know It, we’re doing much more than entertaining. We’re building the core skills of language—sound by sound, word by word—with every beat and every verse.

A Shared Human Tradition

Cultures around the world use music to teach children how to speak.

In Aboriginal communities, lullabies help children learn words tied to land and family.

In France, gentle rhymes like Frère Jacques are used in everyday routines—

with repetition, rhythm, and melody that help children develop speech and memory.

In South Africa, traditional songs often blend music and movement—building language through rhythm and group participation.

It’s not just music.

It’s language, emotion, and connection—passed from one generation to the next.

And every time we sing with a child,

we’re tapping into something timeless and human.

What you are building

As preschool teachers, the songs you sing every day—

Wheels on the Bus, Itsy Bitsy Spider—

aren’t just filling time. They’re building something deeper.

You first heard those same songs as toddlers.

Think about that. That early exposure helped shape your speech—

and your connection to rhythm, melody, and meaning.

And now, you’re passing that gift on to the children you teach—

while also laying the foundation for a lifelong appreciation of music.